Fourier Series - the bridge (periodic signals)

The Fourier Series decomposes a periodic signal in the time domain into a sum of harmonics - sinusoidal components at integer multiples of the fundamental frequency. These harmonics represent the signal's building blocks in the frequency domain.

In other words, a periodic time-domain signal can be perfectly represented by adding together these harmonic sinusoids. Conversely, the Fourier series maps the time-domain periodic signal to discrete points in the frequency domain — its harmonic frequencies.

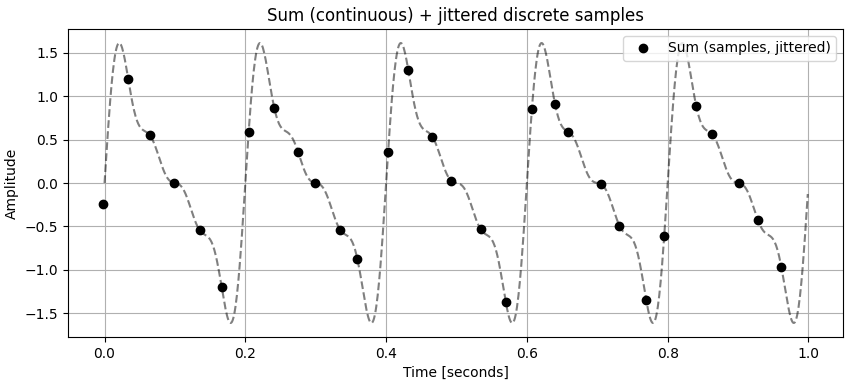

Figure 1: Sum Continuous (High-Resolution) with Actual Jittered Samples Overlaid

View Figure 1's Code

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# === Parameters ===

f0 = 5

T = 1.0

Fs = 30

num_harmonics = 4

amplitudes = [1, 0.6, 0.35, 0.2]

# Time vectors

t_cont = np.linspace(0, T, 1000, endpoint=False)

t_disc = np.linspace(0, T, int(Fs*T), endpoint=False)

t_disc_jittered = t_disc + (np.random.rand(len(t_disc)) - 0.5) * (1/Fs) * 0.5

# Continuous sum

sum_cont = np.sum([A * np.sin(2*np.pi*k*f0*t_cont)

for k, A in enumerate(amplitudes, start=1)], axis=0)

# Jittered discrete sum

sum_disc_jittered = np.sum([A * np.sin(2*np.pi*k*f0*t_disc_jittered)

for k, A in enumerate(amplitudes, start=1)], axis=0)

# Plot

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 4))

plt.plot(t_disc_jittered, sum_disc_jittered, 'ko', label='Sum (samples, jittered)')

plt.plot(t_cont, sum_cont, 'k--', alpha=0.5)

plt.title("Sum (continuous) + jittered discrete samples")

plt.xlabel("Time [seconds]")

plt.ylabel("Amplitude")

plt.grid(True)

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Figure 1 (above) shows a periodic signal plotted over time with discretely sampled points.

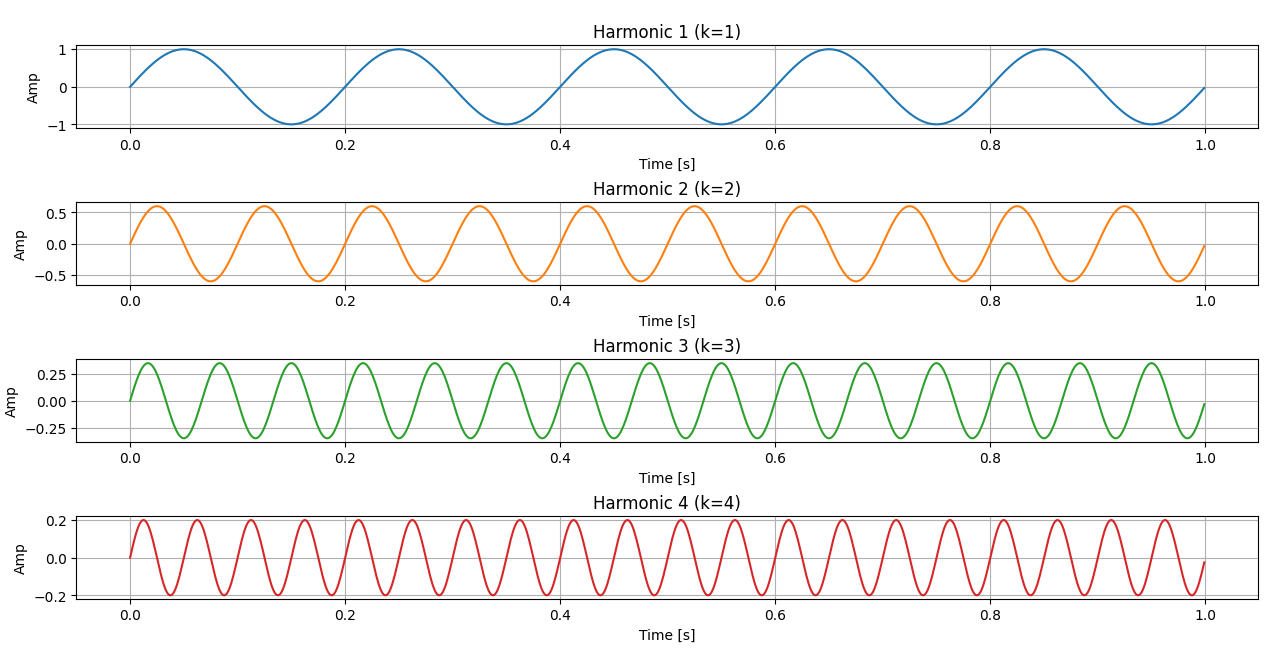

Figure 2 (below) illustrates each underlying harmonic as a continuous sine wave in the time domain.

Figure 2: Underlying Harmonics - Individual Continuous Harmonic Components

View Figure 2's Code

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# === Parameters ===

f0 = 5

T = 1.0

amplitudes = [1, 0.6, 0.35, 0.2]

t_cont = np.linspace(0, T, 1000, endpoint=False)

# Individual harmonics

harmonics = [A * np.sin(2*np.pi*(i+1)*f0*t_cont) for i, A in enumerate(amplitudes)]

# Get the default color cycle from matplotlib

colors = plt.rcParams['axes.prop_cycle'].by_key()['color']

# Plot

fig, axs = plt.subplots(4, 1, figsize=(8, 10)) # 4 rows, 1 column

for i, ax in enumerate(axs):

ax.plot(t_cont, harmonics[i], color=colors[i % len(colors)])

ax.set_title(f"Harmonic {i+1} (k={i+1})")

ax.set_xlabel("Time [s]")

ax.set_ylabel("Amp")

ax.grid(True)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

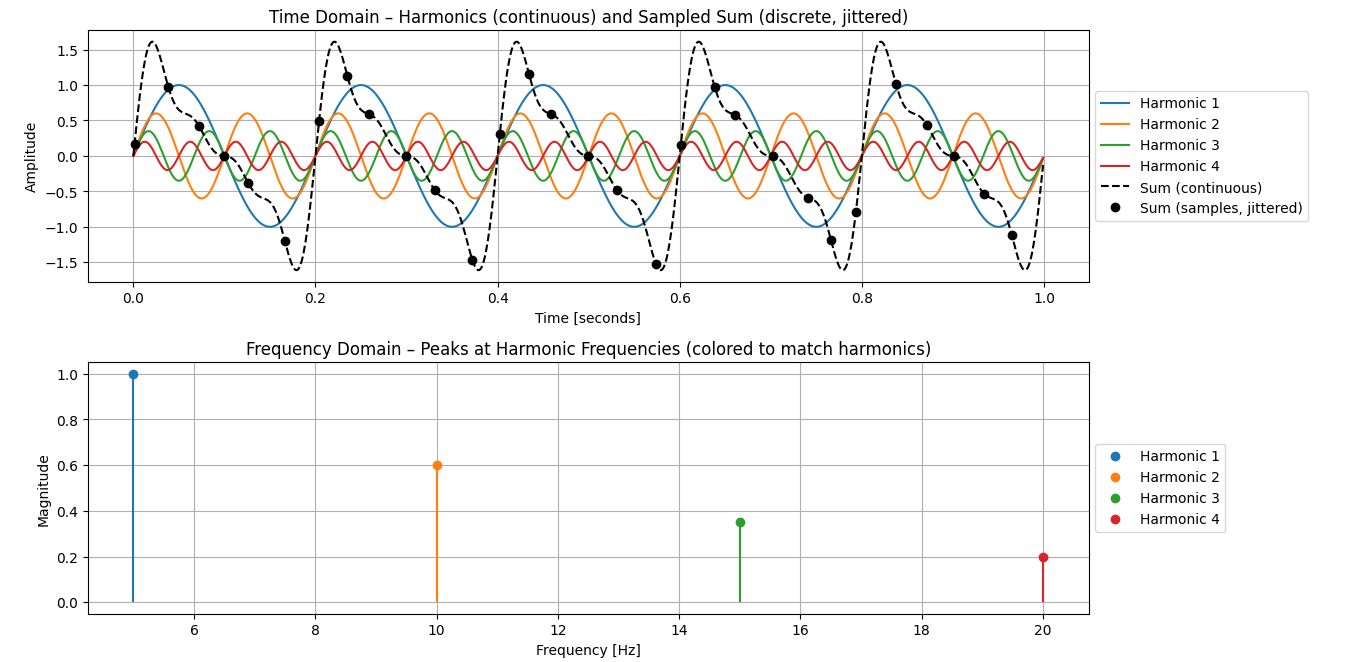

Figure 3: Combined Time-Domain Harmonics with Jittered Samples and Frequency Spectrum

View Figure 3's Code

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# === Parameters ===

f0 = 5

T = 1.0

Fs = 30

amplitudes = [1, 0.6, 0.35, 0.2]

# Colors for harmonics

colors = ['C0', 'C1', 'C2', 'C3'] # matplotlib default color cycle

# Time vectors

t_cont = np.linspace(0, T, 1000, endpoint=False)

t_disc = np.linspace(0, T, int(Fs*T), endpoint=False)

t_disc_jittered = t_disc + (np.random.rand(len(t_disc)) - 0.5) * (1/Fs) * 0.5

# Harmonics and sums

harmonics = [A * np.sin(2*np.pi*(i+1)*f0*t_cont) for i, A in enumerate(amplitudes)]

sum_cont = np.sum(harmonics, axis=0)

sum_disc_jittered = np.sum([A * np.sin(2*np.pi*(i+1)*f0*t_disc_jittered)

for i, A in enumerate(amplitudes)], axis=0)

# Frequencies for Fourier peaks

freqs = np.array([f0*(i+1) for i in range(len(amplitudes))])

# --- Combined figure with subplots ---

fig, axs = plt.subplots(2, 1, figsize=(12, 8))

# Time domain plot

for i, harmonic in enumerate(harmonics):

axs[0].plot(t_cont, harmonic, color=colors[i], label=f"Harmonic {i+1}")

axs[0].plot(t_cont, sum_cont, 'k--', label="Sum (continuous)")

axs[0].plot(t_disc_jittered, sum_disc_jittered, 'ko', label="Sum (samples, jittered)")

axs[0].set_title("Time Domain – Harmonics (continuous) and Sampled Sum (discrete, jittered)")

axs[0].set_xlabel("Time [seconds]")

axs[0].set_ylabel("Amplitude")

axs[0].grid(True)

axs[0].legend(loc='center left', bbox_to_anchor=(1, 0.5)) # legend outside the plot

# Frequency domain plot (colored)

lines = []

labels = []

for i, (freq, amp) in enumerate(zip(freqs, amplitudes)):

markerline, stemlines, baseline = axs[1].stem([freq], [amp], linefmt=colors[i], markerfmt=f'{colors[i]}o', basefmt=" ")

lines.append(markerline)

labels.append(f"Harmonic {i+1}")

axs[1].set_title("Frequency Domain – Peaks at Harmonic Frequencies (colored to match harmonics)")

axs[1].set_xlabel("Frequency [Hz]")

axs[1].set_ylabel("Magnitude")

axs[1].grid(True)

axs[1].legend(lines, labels, loc='center left', bbox_to_anchor=(1, 0.5)) # legend outside the plot

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Figure 3 (above) combines these harmonics (from figures 1 & 2) and shows the signal’s corresponding amplitude peaks at harmonic frequencies in the frequency domain.

The bottom panel in Figure 3 shows the frequency domain representation of the signal, highlighting discrete peaks at the harmonic frequencies corresponding to the sinusoidal components in the time domain.

Block Equation (Fourier Series)

A periodic signal with period can be expressed as a sum of complex exponentials (or equivalently, sinusoids) at integer multiples of the fundamental frequency :

-

indexes the harmonics

- e.g., is the first harmonic , is the second harmonic , etc.

- Hence inside the exponent

note

corresponds to the DC component (), which is not considered a harmonic.

- Hence inside the exponent

- e.g., is the first harmonic , is the second harmonic , etc.

-

are the complex Fourier coefficients representing the amplitude and phase of each harmonic.

- To interpret them:

- Write with and

- Amplitude (magnitude):

- Phase (angle):

- This means the real part measures how much cosine of that frequency is present, the imaginary part measures how much sine, and together they define the sinusoid's amplitude and phase.

- To interpret them:

Understanding Magnitude and Phase of Fourier Coefficients

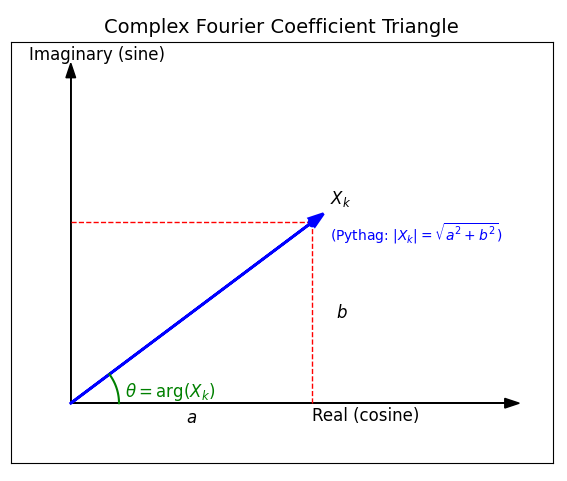

When you see a Fourier coefficient , it's easy to forget what the real and imaginary parts mean. Here's a clear way to visualize it:

Using Euler's formula (), we know that:

- Real part () → corresponds to the cosine component

- Imag part () → corresponds to the sine component

Think of as a vector in the complex plane:

View the above image's code

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

# Fourier coefficient

a = 2.0 # Real part (cosine)

b = 1.5 # Imaginary part (sine)

c = np.sqrt(a**2 + b**2)

theta = np.arctan2(b, a)

# Plot setup

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(7,7))

# Draw axes with arrows

ax.arrow(0, 0, a*1.8, 0, head_width=0.08, head_length=0.12, fc='black', ec='black')

ax.arrow(0, 0, 0, b*1.8, head_width=0.08, head_length=0.12, fc='black', ec='black')

# Draw vector X_k

ax.arrow(0, 0, a, b, head_width=0.08, head_length=0.12, fc='blue', ec='blue', linewidth=2)

# Draw dashed triangle sides

ax.plot([a, a], [0, b], color='red', linestyle='--', linewidth=1)

ax.plot([0, a], [b, b], color='red', linestyle='--', linewidth=1)

# Annotations - outside the triangle

ax.text(a/2, -0.05, r'$a$', fontsize=12, ha='center', va='top') # Real side

ax.text(a + 0.2, b/2, r'$b$', fontsize=12, ha='left', va='center') # Imag side

# Phase angle arc

arc = np.linspace(0, theta, 50)

arc_radius = 0.4

ax.plot(arc_radius*np.cos(arc), arc_radius*np.sin(arc), color='green', linewidth=1.5)

ax.text(0.45, 0.05, r'$\theta = \arg(X_k)$', fontsize=12, color='green')

# Vector tip label

ax.plot(a, b, 'o', color='blue')

ax.text(a + 0.15, b + 0.15, r'$X_k$', fontsize=12)

ax.text(a + 0.15, b + -0.15, r'$(\text{Pythag: } |X_k| = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2})$', fontsize=10, color='blue') # Note

# Axes labels - moved to avoid overlap

ax.text(a, -0.15, 'Real (cosine)', fontsize=12)

ax.text(-0.35, b*1.9, 'Imaginary (sine)', fontsize=12) # moved up

# Set limits and aspect

ax.set_xlim(-0.5, a*2)

ax.set_ylim(-0.5, b*2)

ax.set_aspect('equal', 'box')

# Remove ticks

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

# Title

ax.set_title('Complex Fourier Coefficient Triangle', fontsize=14)

plt.show()

Key points:

- Amplitude (magnitude): This is the hypotenuse of the triangle and gives the overall strength of the sinusoid.

- Phase (angle): This is the angle the vector makes with the real axis — the phase shift of the sinusoid.

- Trigonometric intuition:

Using SOH CAH TOA:

- Opposite side → (imaginary / sine)

- Adjacent side → (real / cosine)

- → angle of the vector

Why this matters:

The real and imaginary parts tell you how much cosine and sine of that frequency are in the signal. Combining them using Pythagoras gives the amplitude, and the angle gives the phase, which shifts the waveform in time. This is exactly how encodes both strength and timing of each harmonic.

- is the fundamental frequency, the lowest frequency of the periodic signal.

Every periodic signal can be “built” by adding together these harmonics. The series tells us exactly how much of each harmonic is present.

Real Fourier Series Form

The Fourier series can also be expressed using only real-valued sine and cosine functions:

- is the DC component (average value of the signal).

- and are the real Fourier coefficients representing the amplitudes of cosine and sine components at the harmonic.

- This form is equivalent to the complex exponential form: so the information about amplitude and phase is fully captured.

Fourier Coefficients (Complex Amplitudes)

The coefficients quantify the contribution of each harmonic in the signal:

- This integral measures how much of the frequency exists in the signal.

- You can integrate over any interval of length , because the signal is periodic.

- In practice:

- gives the amplitude of the harmonic.

- gives its phase (how much it’s shifted in time).

Imagine projecting your signal onto each sine/cosine component — the integral tells you the “shadow” of the signal along that harmonic.

and can be converted to amplitude and phase using: